Icelandic sheep are a mix of adorable and fascinating. During the summer, you can find them roaming freely around the country. For months they are on what seems like the ultimate Icelandic summer vacation – eating, sleeping, and walking wherever they please. Before winter sets in, they are rounded up by the farmers that own them so they can be sheltered from the harsh Icelandic weather.

Regardless of the season, the Icelandic sheep farmer is always at work. If you are interested in hearing a first-hand account of what life on an Icelandic sheep farm is like, I recommend checking out my interview with Pálína Axelsdóttir Njarðvík, creator of the popular Instagram account (@farmlifeiceland). Her account showcases what life on an Icelandic sheep farm life is like from her perspective.

Contents

- Quick facts about Sheep in Iceland

- Icelandic sheep history & heritage

- When is the lambing season in Iceland?

- What is Réttir?

- Sheep farms to visit or stay on in Iceland

- Meat Production of Icelandic sheep

- Wool Production from sheep in Iceland

- How to buy an authentic Icelandic sweater?

- Does Iceland have more sheep than people?

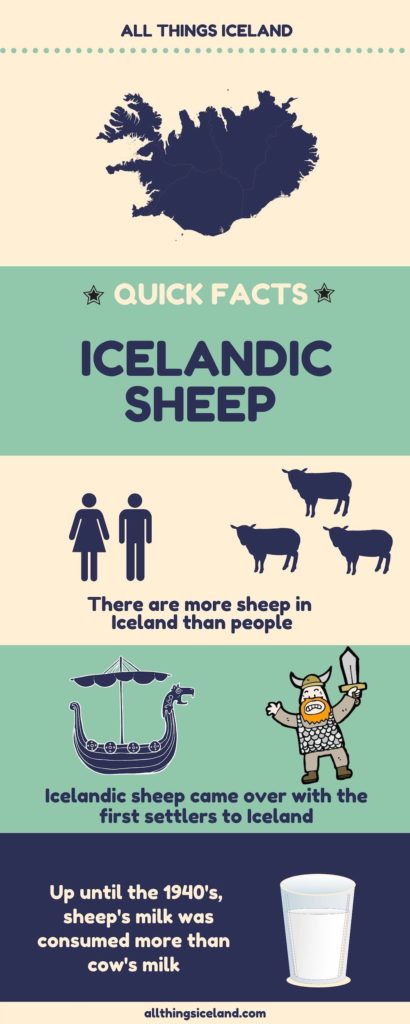

Quick Facts About Sheep in Iceland

- There are more sheep in Iceland than the number of people that live here

- The color of their fleece can be white or a range of browns, grays, and blacks

- Multiple births, such as twins, triplets or more, are very common in this breed because of a gene called Þoka that many Icelandic ewes possess

- Norwegian Spelsau and Icelandic sheep descend from the same stock

- Sheep in Iceland have been bred in isolation for more than a thousand years

- Meat production is the main reason for raising sheep in Iceland

- Sheep milk was once more widely consumed than cow milk in Iceland

Sheep in Iceland have played an important role in the way of life in the country since the first settlers came to Iceland back in the 9th and 10th centuries. I was surprised to learn so many fascinating facts about them after talking to Pálína and doing some research.

Icelandic Sheep History & Heritage

They are classified as Northern short-tailed sheep and are the largest in their group, which includes Finn, Romanov, Shetland, Spelsau and Swedish Landrac. As mentioned in the quick facts above, the Icelandic sheep descends from the same breed as the Norwegian Spelsau.

While it is the case that sheep in Iceland today are pure breeds, at one time farmers did try crossbreeding with foreign breeds. However, those experiments ended because the cross breeding brought on disease. Eventually, all of the sheep that the result of cross breeding were killed, or what is known as culled. Culling is defined as reducing the population of an animal by selective slaughter.

Iceland is notorious for its harsh weather and over the centuries there have been many challenging times for livestock and their farmers. Due to being bred in isolation for more than a thousand years, the Icelandic sheep has been able to thrive in these conditions. Because of that, they are considered to be efficient herbivores.

While sheep are mostly bred for meat in Iceland now, they have contributed to Icelandic society in a variety of ways over the years. Up until the 1940’s, they were the predominant milk producing animal in the country. It was far more expensive to have a cow before that time, so people consumed sheep’s milk instead.

When is the Lambing Season in Iceland?

Lambing season in Iceland starts in May and lasts for about five weeks. During this month, farmers are working around the clock to monitor and assist the ewes (female sheep) who are birthing the cute lambs. Due to a gene that is named Þoka, pregnant Icelandic female sheep often give birth to multiple lambs at once. They can give birth to twins, triplets, quadruplets, quintuplets, and even sextuplets! It is quite amazing to think of that many lambs being born at once.

It isn’t always that the ewes need help with birthing their lambs but it happens often enough that farmers take turns throughout the day and night to check on how everything is going. Normally, lambs are born with their head and front legs coming out first. However, that doesn’t always happen, and that is when a farmer steps in.

Helping Sheep Give Birth is Serious Business

Other times help is needed if the lamb is not breathing or if it is rejected by its mother. When a lamb enters the world, it is crucial that there is a bond between mother and child within the first few minutes. If an ewe is cleaning and drying off their lamb there is a good chance that it has accepted it. Unfortunately, it does happen that an ewe rejects a lamb and starts to ram or kick it.

Pálína talks about this happening to one of her favorite sheep during the interview I did with her. Luckily, she was able to save the lamb and keep it alive by nursing it. Sometimes farmers even find another mother for a rejected lamb. Although it is rare, sometimes an ewe or lamb do not live due to complications in the birthing process.

It might sound sweet that farmers are so attentive during lambing season However, the reality is that the health of the new born lambs and their sheep is essential to their livelihood. It is not to say that the miracle of birth is not appreciated by the farmers. I think it is important to know that the time and effort they put in is a wise investment in their business.

During the summer months, the lambs and sheep head off to roam in the mountains and the countryside until September.

What is Réttir?

Réttir (Rettir) is the annual sheep round-up that happens every September in Iceland. Farmers, their families, friends and tourists go out into the countryside to collect the sheep. Some walk and others travel by ATV or on horseback. Because Icelandic sheep can be anywhere in the countryside, the challenge of collecting them can be quite tedious. I have seen sheep way up on steep mountains and others that have wandered into valleys or the property of others.

If you plan to drive around Iceland during the summer months, just know that sheep will randomly run out into the road. They have the right of way, so please slow down if you see them walking alongside the road. If you do hit a sheep, it is best to call the police (the number is 112) and give them the tag or earmark on the sheep. The police will then contact the farmer, so they can retrieve their sheep.

It used to be that Icelandic sheep outnumbered Icelandic people two to one. However, due to the Icelandic sheep population decreasing and the amount of people living in Iceland increasing, that is not presently the case. Regardless, the sheep still outnumber the amount of people that live on the island. It is hard to fathom but there are hundreds of thousands of sheep that need to be rounded up. The time honored tradition is certainly not for those that are inpatient or physically unfit. It’s a lot of work to round-up sheep but the reward is worth it.

Take Part in a Réttir

If you prefer to not go out to find the sheep but you still want to experience a Réttir, I have great news for you. Some farmers allow for visitors and Icelanders who have no association with a farm to come to the sorting of the sheep.

In different locations around the country during September, there are lists of Réttir sorting times. I went to one in 2019 and it was fascinating. Basically, all of the sheep and lamb that were round-up were put into a big pen. The farmers then find their sheep, which are marked, and put them into a pen that belongs to their specific farm.

What was so cool about this experience for me was that I was able to see Icelandic sheep up close. Normally, sheep run away from humans because they are afraid. There are very few people that interact with sheep and it seems like the sheep would like to keep it that way.

Earlier, I mentioned that there is a reward for the round-up of the sheep, and that is a celebration called the Réttaball. The farmers in each region have parties where they drink, dance, sing and just have a good time because they have finished the monumental task of collecting and sorting their sheep. One event that many people don’t know about is that after the Réttir, many of the lambs are slaughtered. In the month following the round-up, many restaurants and grocery stores are advertising lots of fresh lamb.

Sheep farms to Visit or Stay on in Iceland

If you ever find yourself interested in visiting or staying on a sheep farm in Iceland, there are lists of different farms around the country. There are two in particular that I am going to share because they are primarily sheep farms and you can stay on them, if you wish. I’ve not been to either of them and have no affiliation with the owners.

Bjarteyjarsandur Family Farm

According to their website, “The Bjarteyjarsandur farm is owned and operated by three different families, all specializing in their different fields; i.e. farming, tourism, education, food processing, and machine work. The farm is situated in a beautiful by the fjord with a lovely seashore. The same family has lived in Bjarteyjarsandur since 1887.”

Along with these different experiences, you can eat farm fresh food, cuddle an Icelandic lamb and soak in a natural hot pot by the sea in summertime.

Sölvanes Farm

According to their website “Sölvanes is a traditional sheep farm located in a beautiful valley of Skagafjördur, North Iceland. Sölvanes is very much a family affair, run by Rúnar Máni and his wife Eydís, both from North Iceland. The two sons and other family members play an active part in the family business.”

I’m quite interested in visiting and staying on a farm. I hope to get a chance to do it one day soon, especially since I know that these are family run places.

If you are curious to learn more about these farms, feel free to check out the links in the show notes.

Meat Production of Icelandic sheep

Icelandic sheep are primarily raised for their meat. It’s estimated that about 80% of income from sheep farming comes from selling it. Lamb is a popular export but in recent years it has been found that exporting sheep or lamb meat is not profitable. This is due to the cost of producing the meat in Iceland being higher than the average price obtained for the meat from other countries.

An article in Morgunblaðið, a local newspaper, states a report suggests “that slaughter houses are too many and their numbers need to be reduced to improve efficiency. Reducing the number of meat processing plants could also improve profitability if the slaughterhouses left were able to increase automation.” It might come as a surprise to some but over the years, Icelanders have decreased their consumption of lamb in favor of eating more chicken. Increasing exports of meat is one way that companies are trying to stay in business.

After reading another article about a lamb producer Fjallalamb planning to export lamb to China, I can only assume that there will potentially be a surge in Icelandic lamb exports. Well, if the company is able to figure out how to cut down the cost of production.

As I mentioned in the section about Réttir, the lamb that have been free-roaming around the countryside are slaughtered not long after the sheep have been rounded up for winter. Icelandic lamb is considered some of the best in the world because the animals are not fed any extra grain, given any hormones and are free range.

Wool Production from sheep in Iceland

When settlers came to Iceland back in the ninth and tenth centuries, among other things, they brought sheep with them. Even though sheep’s wool has been used by Icelanders for many centuries, the Icelandic wool industry is only about 125 years old. The company Álafoss was founded in 1896 and had 200 employees at the beginning. At its peak in the 1970’s and 80’s, it employed 2000 people who would process the wool, then knit, sew and make clothes with it. One of the company’s main trading partners was the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Álafoss went bankrupt and the country’s wool industry went down with it.

Resurgence of Wool Production in Iceland

Ístex, which is now the biggest producer of Icelandic wool, started about 25 years ago as a way to revitalize the industry. According to the company, “Ístex was started for the farmers, to keep up their production.”

To give you an example of the amount of wool processed in Iceland, Guðjón Kristinsson, the managing director of Ístex, told the Reykjavík Grapevine back in 2017 that “…there are 500,000 sheep in Iceland, from which the 2000 farmers shear 1000 tonnes of wool a year. This is reduced to 750 usable tonnes after washing; 400 tonnes of the best material is processed into knitting wool, with the second class remainder exported to the UK, mainly for use in upholstery and carpets.”

While Álafoss is still in business and doing well, it is not anywhere near what it was in its heyday. If you are curious about the history of the shop, I recommend visiting. It is only about a 20 minutes drive outside of downtown Reykjavík. It’s off the same road you would take to get to the Golden Circle.

I plan to do a separate episode on the knitting history and culture in Iceland, especially since I recently learned how to knit and am working on my first Icelandic sweater.

How to Buy an Authentic Icelandic Sweater

If you are planning to buy an Icelandic sweater, please make sure that it was made in Iceland. There are many shops that have sweaters that have “designed in Iceland” labels but the wool and manufacturing are from China. They are not authentic Icelandic sweaters. Places like the Handknitting Association of Iceland and Álafoss sell authentic Icelandic sweaters that were produced, designed and knit in Iceland. It helps to keep the local industry going if you buy from shops like the ones I mentioned.

Does Iceland have more sheep than people?

Yes, Iceland has more sheep than people in the country. It used to be that there were two sheep for every one person in Iceland. In recent years, the population of people living here has increased and the population of sheep has decreased. According to an article in the Iceland Review, there were 432,740 sheep in 2018. Sheep numbers were at their highest in 1978. Then, there were over 890,000 sheep! As mentioned earlier, the cost of production of sheep is quite high in comparison to what the farmers are paid, so reducing the number of sheep has cut down on farm operation and production.

Random fact of the episode

Icelandic sheep grow two types of wool. The one closest to their skin is a soft, insulating fiber. While the outer layer is more coarse and protects them against wind and rain. These two layers are combined in Icelandic wool. Wool produced in warmer climates is softer and not as itchy. If you own an Icelandic sweater, you have probably felt itchy if you weren’t wearing a layer between it and your skin. Actually you might still feel itchy but much less than if you’ve had it right next to your skin. Ístex is trying to find ways to reduce the itchiness in the wool fibers.

Icelandic word of the episode

Kind – sheep

Lamb – lamb

I hope you enjoyed listening to this episode of the All Things Iceland podcast. If you think someone else will find this episode interesting and/useful please share it. Recently, I started a newsletter that is dedicated to sharing even more fascinating information about Iceland.

For your convenience and listening pleasure, this podcast is available on many platforms. You can listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcher, and pretty much any platform that plays podcasts.

Let’s be social! Here is where you can connect with me:

Þakka þér kærlega fyrir að hlusta (og að lesa) og sjáumst fljótlega

Thank you kindly for listening (and reading) and see you soon!

amazing thank you very very much

My pleasure and thanks for listening.